Those continuing to claim that he 1926 Cabaret Law was intended to target jazz, Harlem clubs, and interracial clubs evidence classic confirmation bias, and continue to maintain this belief despite evidence that the belief is false. An example is the interpretation of the reference to Runnin' Wild in the comments prefacing the Council adoption of the Law.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one’s prior beliefs or values.[1] People display this bias when they select information that supports their views, ignoring contrary information, or when they interpret ambiguous evidence as supporting their existing attitudes. The effect is strongest for desired outcomes, for emotionally charged issues, and for deeply entrenched beliefs.

Belief perseverance is one form of confirmation bias.(when beliefs persist after the evidence for them is shown to be false).

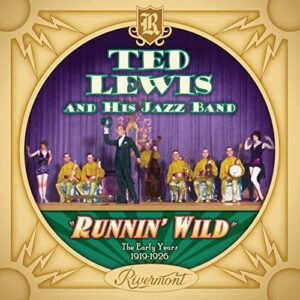

During the summer of 1923, Johnson, along with the help of lyricist Cecil Mack, wrote the revue Runnin’ Wild. This revue stayed on tour for more than five years as well as showing on Broadway. Runnin’ Wild (1921-1926) by James P. Johnson. But, the wildly popular song was played as well by white bands. It became one of the most popular songs of the “Roaring Twenties”. The point is that no one can not belief that the reference to “Runnin Wild” was a reference to the highly popular song, danced to and played by white and black.

The language interpreted was quote by the decision in Chiasson I, 1986:

“The plaintiffs contend that there is no statement of legislative intent which adequately explains this distinction. However, it appears that cabaret licensing was introduced in the city in 1926, as part of an effort to control speakeasies (Recommendation No. 10, Proceedings of Board of Alderman and Municipal Assembly of City of New York [Dec. 7, 1926], at 577). The report of the Committee on Local Laws stated the purpose of the bill: “there has been altogether too much running `wild’ in some of these night clubs and, in the judgment of your committee, the `wild’ stranger and the foolish native should have the check-rein applied a little bit” (ibid.).”

Given the confirmation bias of those seeking to find racist intent (and so as to create a constitutional basis to challenge the law in 2014-17) this language was cited to prove racist intent, without understanding what “Runnin’ Wild” alluded to, and concluding that all “natives” of New York City were black people and that the Flappers dancing to Runnin’ Wild were white and black and the same time.