The Cabaret Law and parallel provision in the City’s Zoning Resolution have evolved over time. This section provides pointers to the history from 1926 to present.

Document Category: Cabaret Law History

Perretti, Burton Nightclub City: Politics and Amusement in Manhatta 2007

Historian Burton Perreti’s 2007 well researched history of New York City nightlife includes a detailed 10-page background of the 1926 Cabaret Law which refutes any claim that the law was directed at Harlem, jazz, and interracial nightclubs. For Mayor Walker, the Cabaret Law was intended primarily to provide a closing time of 3:00 AM and was intended to bring the new nightlife under effective government oversight.

New York Times, June 30, 1926 Article Provides Context as to Running Wild Introduction to Cabaret Law bill.

A New York Times article from June 30, 1926 describes Mayor Walker’s debating the proposed Cabaret Law curfew and providing contemporary color as to “running wild” and “visitors from outside the city” creating disturbances. The contemporaneous account undermines the implied view that the preamble to the enacted law establishes racism.

Sugarman Amicus Letter Refuting Claims of Racist Intent in Original Cabaret Law

Letter Motion to Intervene as Amicus Curiae,

Muchmore Amended Complaint

Muchmore’s Amended Complaint – falsely represented that the thee musician and type of instrument limitations were in the original Cabaret Law.

Festa v. New York City Department of Consumer Affairs -Supreme Court and Appellate Division

in 2004, John Festa and other social dance teachers challenged the constitutionality of the zoning resolution restrictions against dancing, winning in the trial court (Supreme Court), but reversed on appeal “Recreational dancing is not a form of expression protected by the federal or state constitution ” Litigation brought by Paul Chevigny.

Runnin’ Wild – Most Popular Song of the Roaring Twenties – Confirmation Bias

Those continuing to claim that he 1926 Cabaret Law was intended to target jazz, Harlem clubs, and interracial clubs evidence classic confirmation bias, and continue to maintain this belief despite evidence that the belief is false. An example is the interpretation of the reference to Runnin’ Wild in the comments prefacing the Council adoption of the Law.

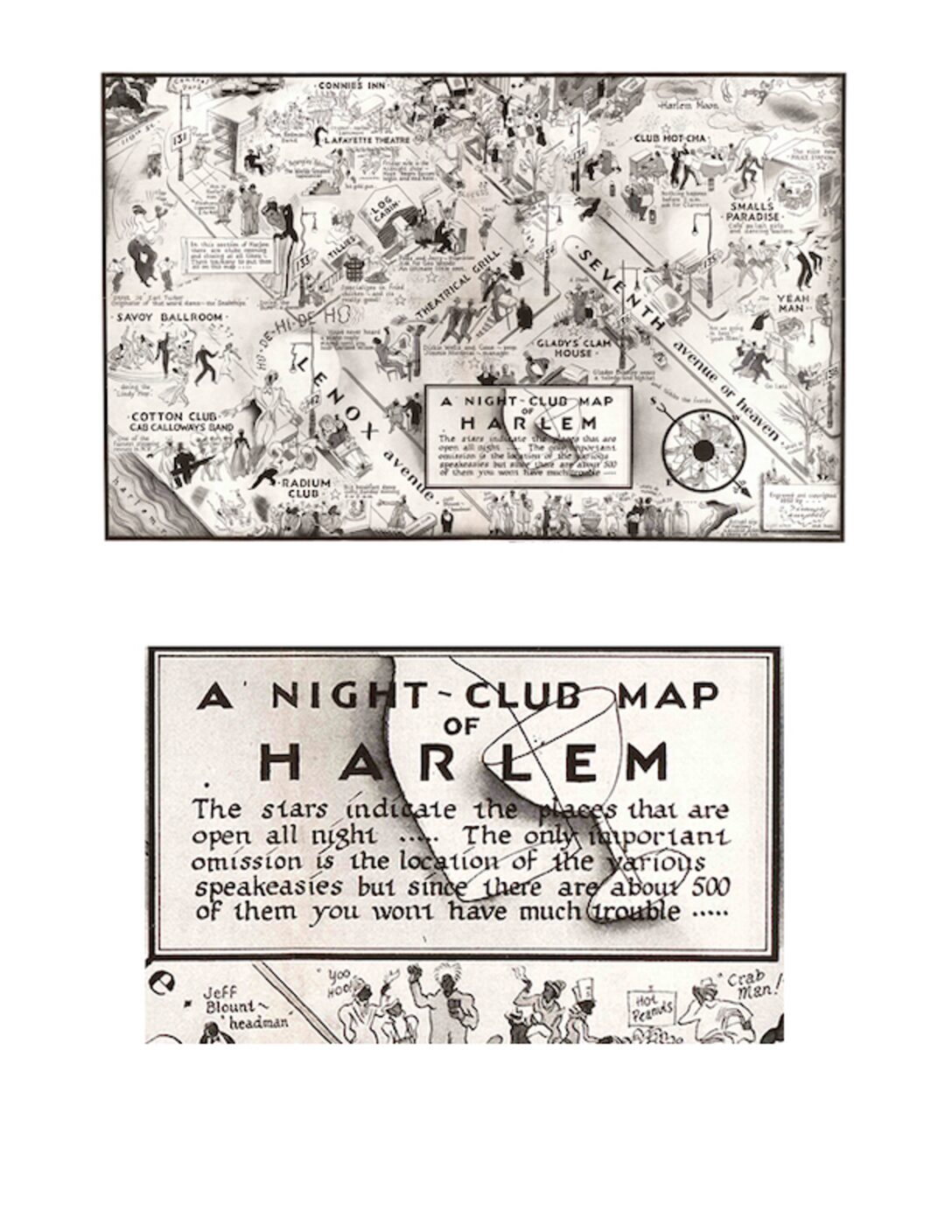

A Night Club Map of Harlem – Campbell, E. Simm

If one gives credence to those who claim that the 1926 Cabaret Law was intended to close down Harlem night clubs, this well known 1932 drawing/map shows the thriving club scene in Harlem, only mentioning the 500 speakeasies.

The Cabaret Law did not target black venues when allegedly not allowing jazz instruments in non-licensed establishments.

When challenged, those having a belief that the Cabaret Law was racist justify their belief by claiming that the Cabaret Law allowed classical music instruments playing in non-licensed establishment, and prohibited typical jazz instruments thereby targeting black establishments. There are several problems with this claim: those provisions were placed in the Cabaret Law in 1961 as a way to liberalize the law allowing some live musical performance. This belief ignored the large number of non-black musicians playing jazz during the Jazz Age and the Flapper era. The second reason oft cited for this belief in the language to the introduction of the 1926 bill.

1926 Cabaret Law as Enacted

1926 Cabaret Law: A LOCAL LAW to regulate dance . halls and cabarets, and providing for licensing the same. Very many have opinions and views about the 1926 Cabaret Law, but never have read the law, since it is not available on databases such as Westlaw and Lexis. We obtained the text of the law here from the Archives of the City of New York. Many claim the law was racist and was aimed at black jazz venues was their mistaken belief that the 1926 Law supposedly included a restriction prohibiting drums and saxophones in cabarets. But, such a provision was not added until 1961, and was a relaxation of the law to allow stringed instruments including guitars and violins.